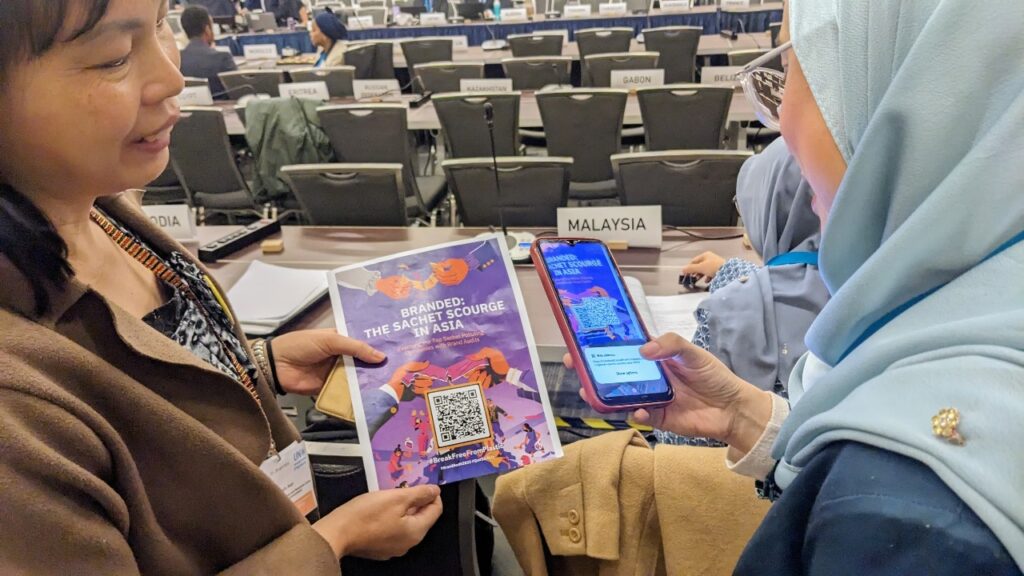

The pressure was on at INC-4, the penultimate round of talks planned to create an international, legally-binding treaty to end plastic pollution. With the clock ticking after the three previous sessions failed to make any substantial progress, member states finally got down to discussing the content of the treaty.

Over the seven days (23 – 29 April 2024) in Ottawa, delegates were able to “streamline” some of the proposed text but, with a deluge of new additions and brackets (which show disagreement with the words placed inside), in the end they were left with a draft that is nowhere near ready for negotiations at the final session in Busan, Korea in November 2024.

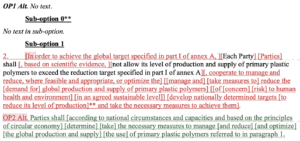

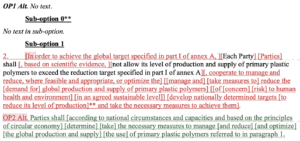

A snapshot of the INC-4 streamlined text: all words in brackets have been objected to by at least one member state.

Aware of the amount of work still to do, member states did agree on creating a legal drafting group to help clarify the text of the future agreement. This is much needed because there are now at least 3,686 brackets in the text, making it almost unintelligible.

Countries also agreed to establish two expert working groups that would convene before November to discuss certain aspects of the treaty such as chemicals of concern, product design and financial support. Notably not up for discussion before INC-5 are primary plastic polymers, what Rwanda called “the elephant in the room”. An attempt to create such a working group, which would consider cuts in plastic production was disappointingly rejected at the last minute. This means it will be difficult, though not impossible, to include production caps – the key to ending plastic pollution – in the final treaty.

As is now the norm at INC meetings, a small number of countries continued to obstruct and delay discussions. They attempted to narrow the scope of the treaty to waste management (instead of the full lifecycle of plastic, as mandated) and remove all references to production, chemicals of concern, producer responsibility, human rights and microplastics.

One delegate said that every single material can release particles into the air – even skin – so plastics should not be singled out. Others denied the existence of scientific evidence of human health impacts, suggested wording to acknowledge the ‘critical role plastic plays in sustainable development’ and cautioned against any ‘sudden transition’ away from plastic.

This kind of bad faith negotiation can only be prevented by a strong conflict of interest policy and the right for member states to vote on decisions. The goal of the plastics treaty is to find solutions to a shared crisis caused by a minority of bad actors. But if these actors are present and demanding all text needs their approval, how can we ever hope to achieve this?

Highlights

Juliet Kabera, Rwanda

The highlight of the seven days was a strong push for a limit on new plastic production, championed by Peru and Rwanda. Their proposal to adopt a global target to reduce 40% of the global use of primary plastics polymers by 2040 from 2025 levels, was supported by at least 29 member states during the meeting.

Following the proposal, these countries launched the Bridge to Busan Declaration on Plastic Polymers to rally INC delegates to support reducing primary plastic production ahead of INC-5.

There was a strong presence of rightsholders at the meeting, including the Indigenous Peoples Caucus, waste pickers, women, workers and youth organisations. Rightsholders are different to stakeholders because they possess internationally recognised human or collective rights that will be impacted by the outcome of the treaty. They made moving interventions during the meeting and led the “March to End the Plastic Era” through the city.

There was a strong presence of rightsholders at the meeting, including the Indigenous Peoples Caucus, waste pickers, women, workers and youth organisations. Rightsholders are different to stakeholders because they possess internationally recognised human or collective rights that will be impacted by the outcome of the treaty. They made moving interventions during the meeting and led the “March to End the Plastic Era” through the city.

Various global bodies were also present, with the World Health Organisation (WHO), recommending that the use of plastic for medical and healthcare should not be exempt from the treaty and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights calling for a reduction in plastic production, saying that “any person that is given a choice, will chose nature over destruction.”

Low points

There was a clear increase in industry interference in the treaty negotiation process. We saw everything from paid advertising around the venue extolling the virtues of plastic, to reports of harassment and intimidation from the independent Scientists Coalition. There were many industry-sponsored events, including one from the world’s biggest producer of PET resin called “Friends of Zero Waste”, while reps from plastic manufacturers and trade bodies sat alongside members of official government delegations in the negotiating rooms.

There was a clear increase in industry interference in the treaty negotiation process. We saw everything from paid advertising around the venue extolling the virtues of plastic, to reports of harassment and intimidation from the independent Scientists Coalition. There were many industry-sponsored events, including one from the world’s biggest producer of PET resin called “Friends of Zero Waste”, while reps from plastic manufacturers and trade bodies sat alongside members of official government delegations in the negotiating rooms.

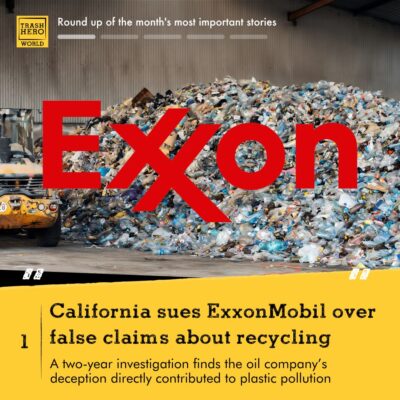

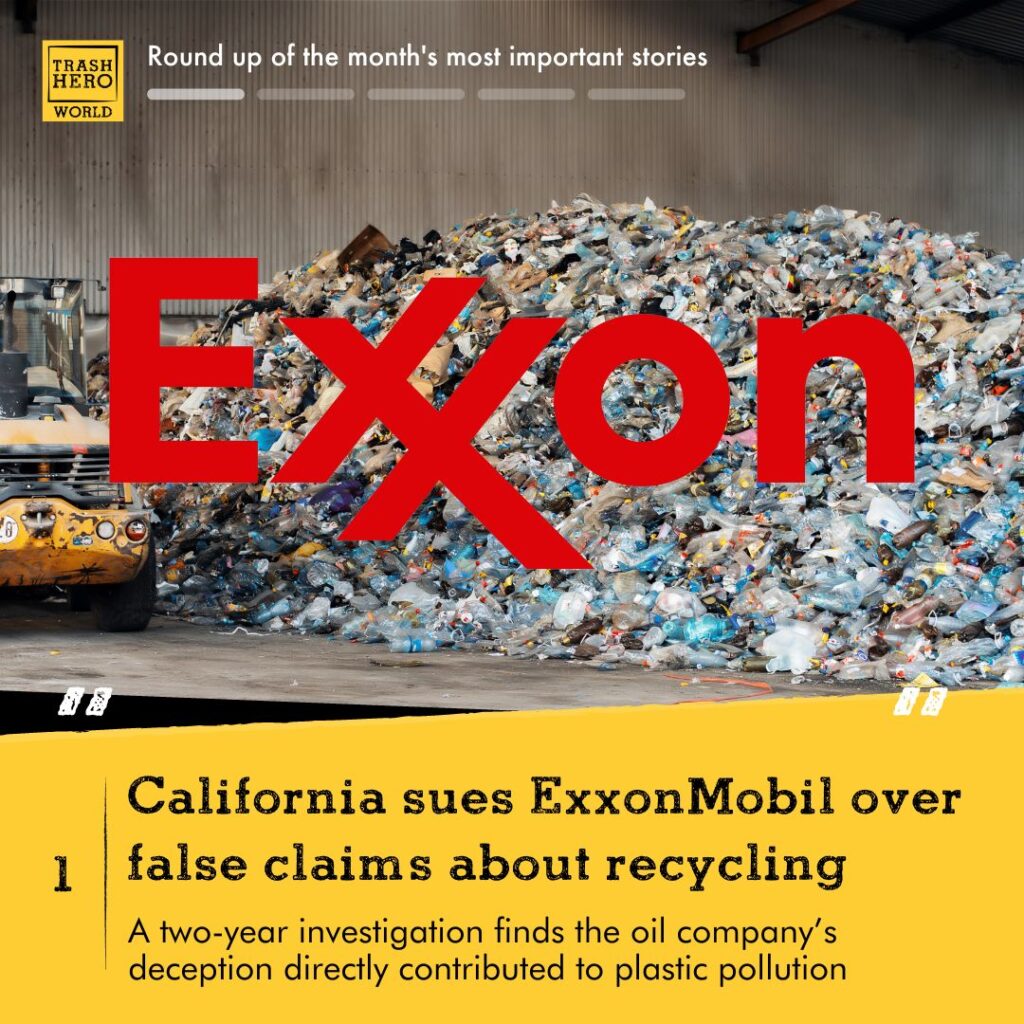

The industry lobbying and spread of misinformation to member states was coordinated and calculated. As a result, one of the topics for intersessional work is “enhancing recyclability”, despite clear evidence of the threats to health and the environment from the mixing and concentration of chemical additives during the recycling process.

Analysis by CIEL of the published list of INC-4 participants revealed that 196 lobbyists for the fossil fuel and chemical industry were registered for the event – a 37% increase over the previous meeting six months ago. With side events and informal meetings, many more were likely present.

What happens now

In the final session of INC-4, which ended in the small hours of the morning, countries decided to prioritise intersessional (preparatory) work on:

In the final session of INC-4, which ended in the small hours of the morning, countries decided to prioritise intersessional (preparatory) work on:

1) how to finance the implementation of the treaty;

2) assess the chemicals of concern in plastic products; and

3) look at product design, reusability and recyclability.

Other parts of the treaty – including primary plastic polymers, microplastics and extended producer responsibility – were not assigned any time or resources.

Member states agreed to let observers participate in this work. The composition and the schedule of the working groups is yet to be decided.

Additionally, they decided to create a legal drafting group that will conduct a legal review of the text and provide recommendations for the next meeting.

The big two open questions of the negotiation process remain open: will the INC listen to calls for a clear conflict of interest policy to stop the future treaty being derailed by the petrochemical lobby? And will they protect the right to vote on all decisions, so that it does not get watered down?

The big two open questions of the negotiation process remain open: will the INC listen to calls for a clear conflict of interest policy to stop the future treaty being derailed by the petrochemical lobby? And will they protect the right to vote on all decisions, so that it does not get watered down?

As Graham Forbes, global plastics campaign lead at Greenpeace put it: if member states “don’t act between now and INC-5 in Busan, the treaty they are likely to get is one that could have been written by ExxonMobil and their acolytes.”

Image credits: all photos taken inside the INC-4 venue by IISD/ENB – Kiara Worth

read more