This is the question we get asked the most by our cleanup participants. After doing the hard work of picking it up, it’s natural to want to find out what happens next!

No easy answers

In almost all cases, the trash is handed to the municipality to manage, according to the waste management infrastructure in place locally. In other words, we move it from one place to another. Wherever possible, our volunteers will first sort the collected waste, separating any recyclable and reusable material. What gets separated will depend on the local facilities, but the pile is always far smaller than people imagine. And they are usually surprised to learn that the few types of “recyclable” plastic may not get recycled at all and can only be recycled once or twice – often with serious health risks – before it gets thrown away.

In almost all cases, the trash is handed to the municipality to manage, according to the waste management infrastructure in place locally. In other words, we move it from one place to another. Wherever possible, our volunteers will first sort the collected waste, separating any recyclable and reusable material. What gets separated will depend on the local facilities, but the pile is always far smaller than people imagine. And they are usually surprised to learn that the few types of “recyclable” plastic may not get recycled at all and can only be recycled once or twice – often with serious health risks – before it gets thrown away.

This is an opportunity to reflect that, even in areas where glass, metal and paper are easily recycled, there really is no good solution for plastic packaging.

This is an opportunity to reflect that, even in areas where glass, metal and paper are easily recycled, there really is no good solution for plastic packaging.

In all locations, some form of landfill or incineration remain the default for the non-recyclable waste. Both of these options have serious health, social, environmental and climate impacts, even in developed countries like Switzerland.

Reframing the question

With no good answer to the question “where does the trash go?”, we can conclude it’s critical to reduce the waste being produced in the first place. So we ask a different question – “where does the trash come from?” – instead. There is a widely-held belief that the current plastic pollution crisis is caused by irresponsible people who litter and / or poor waste management. People who join our cleanups are often unaware that this is an industry-marketed fiction. Through our cleanups, we try to move the conversation towards the real causes of the crisis – poor packaging design and delivery systems, overproduction and the lack of regulation or producer responsibility. These wider systemic problems are the real source of the pollution – not the weekend picknickers.

With no good answer to the question “where does the trash go?”, we can conclude it’s critical to reduce the waste being produced in the first place. So we ask a different question – “where does the trash come from?” – instead. There is a widely-held belief that the current plastic pollution crisis is caused by irresponsible people who litter and / or poor waste management. People who join our cleanups are often unaware that this is an industry-marketed fiction. Through our cleanups, we try to move the conversation towards the real causes of the crisis – poor packaging design and delivery systems, overproduction and the lack of regulation or producer responsibility. These wider systemic problems are the real source of the pollution – not the weekend picknickers.

In some areas, after a cleanup we might also examine and record the brands on the plastic trash collected, to highlight the link between producer decisions and pollution. This “brand audit” data is also shared with organisations such as Break Free From Plastic for research and advocacy work.

“Upcycling” and “recovery”?

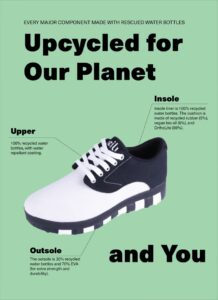

People often ask why we don’t “upcycle” the trash or collaborate with companies who say they “recover ocean-bound plastic“, sometimes as part of a credit scheme. The reason is that these are false solutions. At best they distract from the real actions needed; in the worst case scenario they create new problems or enable greenwashing by companies that have the power to make far more impactful changes.

Shop to save the planet: is producing more stuff really the way out of a crisis caused by overproduction?

What do we mean by this? So-called plastic “upcycling” is really “downcycling” – creating objects that cannot be recycled further, using additional new resources. This only delays disposal of the material in a landfill, incinerator or worse, while creating microplastics and potentially hazardous chemical cocktails in the process.

Suggesting these recycled products use material “recovered” from the ocean without any proof can add an additional layer of greenwash. In reality, most plastic pulled from the sea is too degraded to be recycled. But with some creative accounting or vague labelling producers can claim packaging is 100% made from this source.

Both “upcycling” and plastic “recovery” are almost always presented as a solution for plastic pollution, which leads people to think that it is okay to keep producing and using plastic at current rates. It’s common for the plastics industry to focus attention on these kinds of false solutions, rather than take more helpful steps to reduce their production of single-use plastic. We don’t want to be part of this misinformation.

Local downcycling

We do however support some small, locally-based initiatives to deal with existing waste, if they fit certain criteria.

Some Trash Hero chapters donate non-recyclable trash to local entrepreneurs who use it as raw materials to make different things. This is typically on islands or in rural areas where the alternative is often open burning. As long as there are no better options for the waste and no greenwashing is involved, downcycling into durable and relatively safe products using minimal additional resources can be a practical, if temporary solution for existing waste. While these actions can’t solve the plastics crisis long term, they don’t get in the way of the solutions that will lead to a truly safe and circular economy.

From left: shoes collected at cleanups are downcycled into new flip-flops by Tlejourn; straws are donated to create filling for wheelchair cushions; a sculpture created for a festival in Thailand; collected cigarette butts are displayed in Zurich

On a smaller scale, we have also worked with artists who make sculptures and other works from trash to draw attention to the problem of plastic pollution. This is different from artists who try to create beauty from plastic waste, which again feeds into the narrative that it is okay to keep increasing production of this toxic, climate-damaging material.

The bottom line:

The answer to “where does the trash go?” is “nowhere good”. We must instead look at “where does the trash come from?”. We need to reduce the amount of materials we use in the first place, make them safe and keep them in use – through reuse infrastructure, not recycling – for as long as possible. Only by supporting zero waste systems and lifestyles will we be able to stop picking up trash every week.

Join the conversation