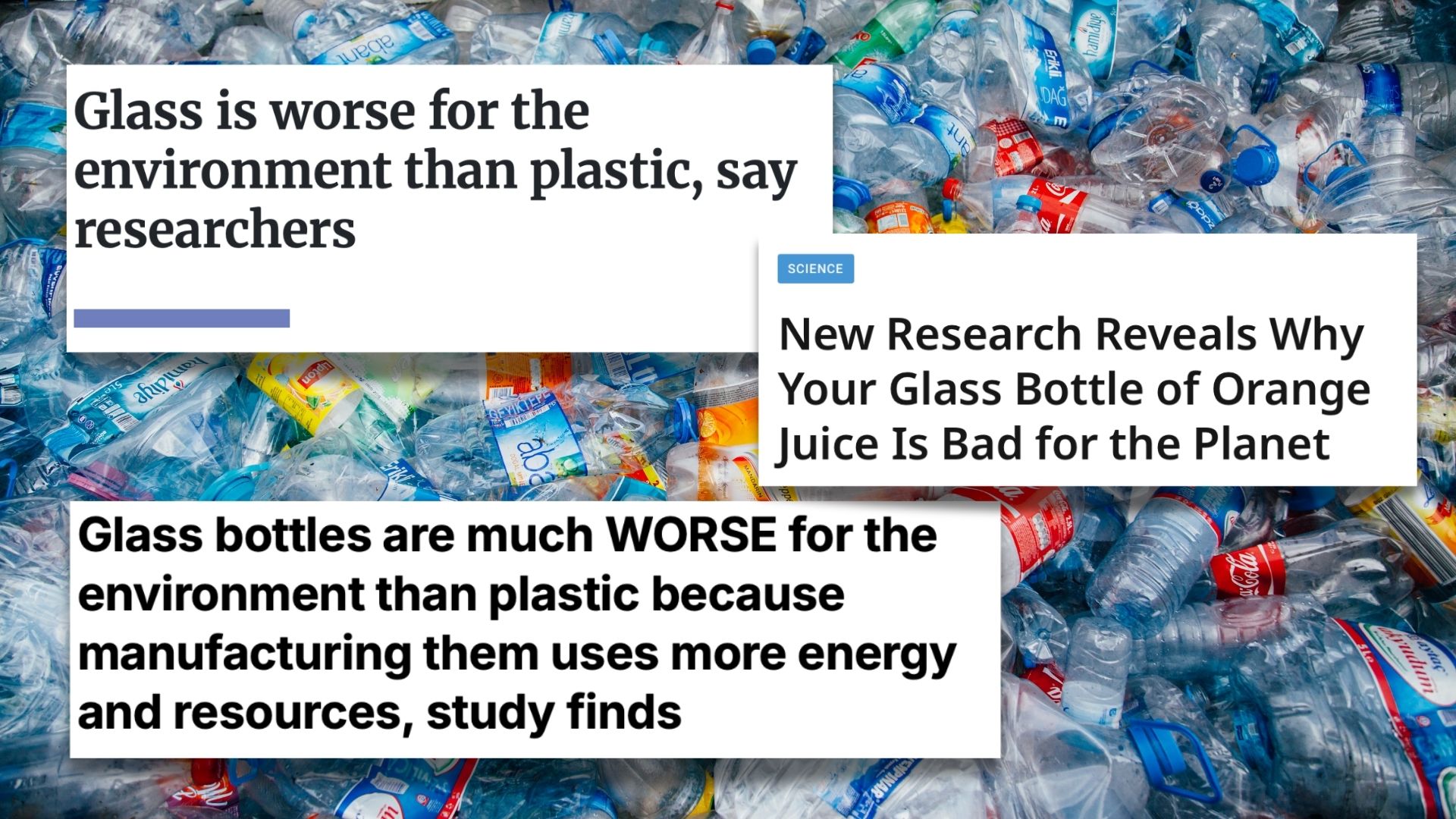

We often hear that plastic bottles or packaging are more “eco-friendly” than their glass counterparts, primarily because plastics are lighter and (so the argument goes) create fewer greenhouse gas emissions in production and distribution. But a closer look at these “life cycle assessments” (LCAs) makes it clear that this narrative is flawed in several fundamental ways. In particular, work by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Life Cycle Initiative has shown that focusing only on a narrow set of impacts obscures the broader environmental harms of plastics and fails to capture the advantages of reuse systems.

So what are the pitfalls of the “plastic is greener than glass” claim?

1. Narrow focus on climate impacts

Many “plastic versus glass” studies focus on one core metric: carbon or greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Because plastics are lighter and require less energy for transport, they often appear to have a lower carbon footprint than glass, at least in the framing used by the researchers.

But climate impact is only one of many categories a robust environmental assessment should cover. Other key impact areas – toxicity, biodiversity loss, ecosystem degradation and the social or justice dimensions of pollution (harms to communities, waste pickers, Indigenous Peoples) – are often downplayed or excluded entirely as they are difficult to measure and quantify.

Plastic LCAs for example typically omit leakage into the environment, which happens at all points in its life cycle – from pellet spills (the second largest source of microplastics in the ocean) to shedding and leaching during use and litter. Leakage is one of the most damaging and irreversible impacts of plastics, leading to ingestion by wildlife, entanglement, fragmentation into persistent microplastics and cumulative ecosystem harm.

2. Over-reliance on LCAs as a decision-making tool

LCAs, as noted above, are not designed to capture the full system of impacts. They need to be supplemented with additional studies and knowledge to give a full picture.

But even the insights they provide using indicators such as energy and water use, or emissions and resource extraction, should not be taken at face value. The system boundaries and assumptions in each study make a huge difference: what production processes, what end-of-life scenarios, what transport distances, what reuse rate have been assumed? Minor shifts in assumptions can flip the results.

LCAs can also, intentionally or not, hide “burden-shifting”: improving one impact category (e.g., lowering GHGs) may worsen another not included in the study (e.g., ecotoxicity, microplastic release). Indeed, the UNEP meta-study warns, “like any tool, [an] LCA does not replace the need to draw upon a range of information sources when making decisions.”

So when someone cites an LCA that says “plastic is better for the climate”, the key questions are: “what have they left out? What were their assumptions? What alternatives did they model? And do those reflect the system we could realistically move towards?”

3. False comparison: single-use glass vs single-use plastic

Another shortcoming of many LCAs is that they compare single-use glass with single-use plastic, with the typical end-of-life scenario being recycling. In reality, glass can be reused tens if not hundreds of times before needing to be recycled.

Why does this matter? Because reuse avoids the vast majority of any material’s climate impacts, particularly the energy-intensive melting process of glass. Instead, reuse only requires washing, drying and local transport. These impacts are far lower, and are declining further as energy grids decarbonise and reverse-logistics systems improve. Meanwhile plastic production remains closely linked to fossil-fuel extraction and refining, global supply chains, and a poor 9% recycling rate, much of it shipped to countries in the Global South.

In short, if we make a more realistic comparison between single-use plastic and reusable glass, the advantage swings firmly towards glass plus reuse systems.

4. Ignoring business models and system design

A major methodological flaw in many LCAs is the assumption that the business model will be the same for the existing and replacement materials. That is, they compare plastic bottles shipped long distances to glass bottles shipped in exactly the way. But what if that’s not the way it would work?

For example, if we slot heavy glass bottles into a conventional global production-and-distribution model, they will naturally perform worse than plastic if shipped halfway around the world for a single use. That’s because this model was built around and optimised for single-use plastics. But glass functions best with local bottling and refilling, reverse logistics, and much smaller distribution networks.

If the comparison privileges the status quo, rather than the alternatives we may prefer to cultivate, it skews the results. If we want a better system (reuse and refill within local networks) then this is what should be modelled. A comparison of materials within the existing system is not going to make sense.

5. The broader issue: redefining “eco-friendly”

Ultimately the myth that “plastic is greener than glass” stems from a too-narrow definition of what “eco-friendly” means. If we define it purely as “the lowest carbon footprint in today’s system”, plastics could emerge as a winner. But if we define it in a way that includes:

– chemical toxicity

– persistent pollution and ecosystem damage

– leakage and microplastics

– resource circularity

– reuse potential

– environmental justice

– future-proofing (energy decarbonisation, logistics innovation)

then the narrative changes dramatically.

The UNEP/Life Cycle Initiative recommendation emphasises this clearly: the priority is reuse, reducing single-use products, and system redesign, regardless of the material.

➤ Cut through the greenwashing

When you see a claim that “plastic is greener than X material” ask these questions:

– What impacts were assessed (just GHGs, or also (eco)toxicity, persistent pollution and social / health outcomes)?

– What was the alternative material and was it reused or used once and recycled?

– What system design assumptions were built in (transport distances, reuse, decarbonised energy)?

– What life-cycle boundaries were applied (upstream fossil-fuel extraction, pellet loss, end-of-life leakage)?

And lastly: what if we changed the system, would the result still favour plastic?

When the full picture is taken into account, the “plastic is greener than glass” claim collapses. The more constructive agenda is not material substitution alone, but system change: moving away from single-use, designing for circularity and investing in local infrastructure enabling safe reuse, refill and repair.

Further reading:

Are LCAs greenwashing plastic?

A review evaluating the gaps in plastic impacts in life cycle assessment

How life-cycle assessments can be (mis)used to justify more single-use plastic packaging

Join the conversation