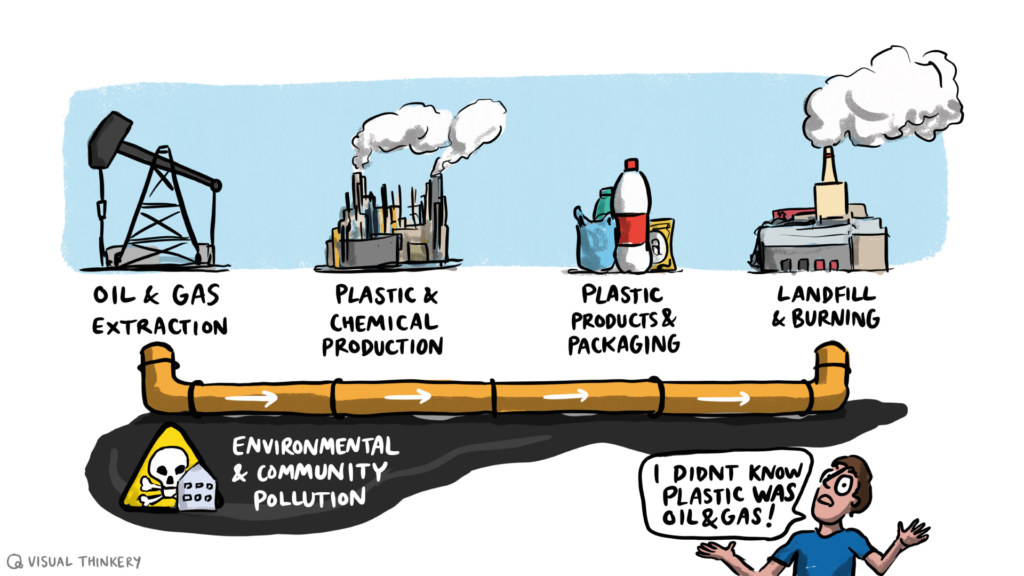

A fascinating new report, ‘Winter is coming’ by Break Free From Plastic and CIEL, explores how the ongoing fuel crisis is linked to the plastics industry.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has affected energy supplies and, consequently, prices worldwide. This is especially true for European countries that rely on Russia for oil and gas – in 2020, Russia supplied 38% of the EU’s gas and 22% of their oil. By August 2022, it became clear to the EU that they were facing a severe energy crisis and limited supplies of oil and gas meant that prices continued to soar. There have been warnings of power cuts lasting up to 3 hours to try and save energy, and millions of people are concerned about how they can afford to stay warm over what could be a freezing winter.

In response to these concerns, the EU set a target for all member countries to reduce their energy consumption by 15% by 31 March 2023. To help achieve this, governments have been advising consumers about how they can reduce their energy use. For example, Germany recommended that its citizens take cold showers and limit the use of their heating. However, industrial use of oil and gas continues unabated, with no government advice or restrictions to date.

So how does this relate to plastic?

Currently, the plastics industry is the largest consumer of oil and gas in the EU, accounting for 8% and 9% of the EU’s final consumption in 2020, respectively [efn_note]Page 4, ‘Winter is Coming‘ [/efn_note] . It overshadows any other industry, including steel, automobile manufacturing, machinery, food, and beverages. Within the plastics industry in the EU, over 40% of end-market plastics produced are instant waste – single-use plastic packaging.

The EU and its member states have been leaders in tackling the plastics crisis. In 2018 the EU released its Plastics Strategy, which aims to ‘transform the way plastic products are designed, produced, used and recycled’ and is described as ‘a key element of Europe’s transition to a circular economy’ [efn_note]European Commission Plastics Strategy [/efn_note] . In 2019 they announced the Single Use Plastics Directive that set a collection target of 90% for recycling single-use plastic bottles by 2029. [efn_note] European Commision Single Use Plastics Directive [/efn_note] This leadership was particularly evident at the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) in March 2022, when there was a historic advance in negotiations for a global agreement to tackle plastic pollution.

Despite all that the EU has tried to do to reduce plastic pollution, there has been no mention of placing a cap on the production of unnecessary plastic or restricting the activity of the petrochemical industry. This, despite their significant contribution to climate change and their continuing depletion of precious oil and gas reserves.

The report found that if plastic packaging was reduced by 50% and the target of 90% recycling was achieved, this would lead to a reduction of 6.2 billion cubic metres (bcm) of fossil gas and 8.7 million tonnes of oil at the EU level compared to 2020. These figures are equivalent to the oil and gas consumption of the entire Czech Republic in 2020.[efn_note] Page 5 ‘Winter is Coming‘[/efn_note]

The report concludes that, rather than seeking new trade deals for fossil fuels, this situation presents the EU with a unique opportunity to address the energy, climate and plastic crisis. Immediate and drastic action should be taken to reduce the production of unnecessary and excessive virgin plastic by implementing the Plastics Strategy from 2018 and the Single Use Plastics Directive from 2019. In turn, this would significantly reduce greenhouse emissions, reduce plastic pollution and free up the limited energy supplies. The oil and gas that would have been used to produce plastic could instead supply millions of people with reliable and more affordable energy over the winter.

You can read the Executive Summary of the report or the full report.

Footnotes & further reading:

read more

WHERE DO THEY GO?

WHERE DO THEY GO? HEALTH RISKS

HEALTH RISKS ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS

ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS ALL OF THIS IS AVOIDABLE!.

ALL OF THIS IS AVOIDABLE!.

A more likely scenario for ‘end of life’ is that the bottles end up either in landfill, burned openly or in an incinerator to “recover energy”, or discarded on land or in water (the bottles pictured, left, were collected at a single Trash Hero beach cleanup in Koh Lanta, Thailand).

A more likely scenario for ‘end of life’ is that the bottles end up either in landfill, burned openly or in an incinerator to “recover energy”, or discarded on land or in water (the bottles pictured, left, were collected at a single Trash Hero beach cleanup in Koh Lanta, Thailand).