INC-5.2 was a failure of process, not of outcome

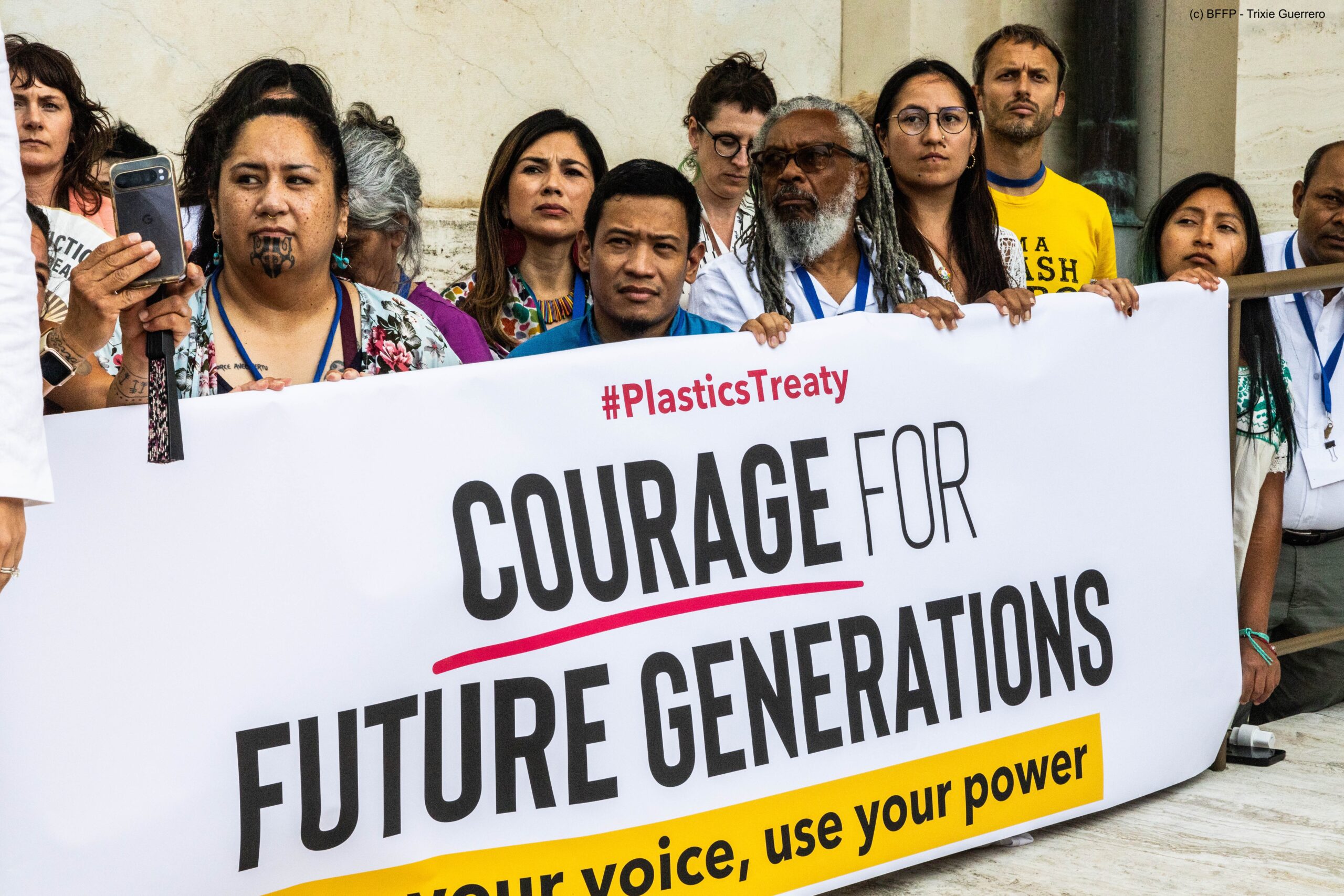

Billed as the make-or-break moment in a process launched in 2022, the sixth round of negotiations on a global plastics treaty (INC-5.2) ended on 15 August in Geneva without agreement, leaving the whole process in limbo.

To many of us involved it was a bitter blow, yet the collapse was far better than the alternative. Headlines proclaimed the talks a “failure”; but if there was a failure in Geneva, it was (again) one of process, not of outcome.

From the outset, the plastics treaty negotiations have been held hostage by a small but powerful group of petrostates, wielding a procedural rule as their weapon. This rule, favouring consensus-based decision making, has allowed them to veto any measures that would reduce plastic production – the key to addressing pollution, according to the majority of states.

At INC-5.2, the Chair, Ambassador Luis Vayas Valdivieso, again struggled to break this deadlock and – at the eleventh hour – took the decision to table a weak compromise text. The hope was that countries present would accept it rather than leave with nothing.

But the treaty text read like an industry wishlist, and was rightly rejected by the ambitious majority. That refusal was a victory: it prevented the world being trapped in a hollow agreement and has kept open the possibility of negotiating something stronger.

Read our full report on INC-5.2 below.

Ambition meets obstruction

Hopes going into Geneva were tempered by the scale of the challenge. The procedural wrangling and stalled progress of the previous five rounds of talks had made it clear that a new approach would be needed if a treaty was to be finalised. Although a long shot, many observers remained cautiously optimistic that a call for a vote to override obstruction was possible.

A record 184 countries took part, joined by civil society organisations, scientists and Indigenous leaders. But industry presence was larger than ever: analysis from CIEL counted 234 officially accredited lobbyists from the fossil fuel and petrochemicals sector at the talks, many embedded within state delegations. Their influence was felt throughout: reinforcing the positions of oil-producing states; spreading disinformation; and even occupying limited seats in meeting rooms to keep rightsholders out.

They also succeeded in keeping the same dead end process in place. The vast majority of discussions were again held behind closed doors, denying rightsholders full and equitable participation. Even some member states complained of unclear scheduling, lack of seating and access to microphones.

These tactics only deepened the sense that the integrity of the talks was being compromised and undermined by well-coordinated obstruction. Calls for a conflict of interest policy have been consistently sidestepped by the INC secretariat.

In the face of this, civil society and rightsholder groups present in Geneva mobilised rapidly, staging several actions in- and outside the UN throughout the two weeks to remind negotiators to “fix the process, keep your promise and end plastic pollution.”

Parallel red lines

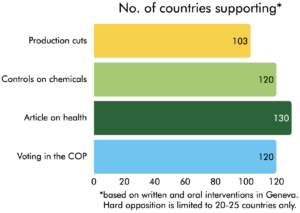

From the opening days, it was clear that the fundamental fault line – the relentless production of plastic and toxic petrochemicals – had not shifted, with countries putting their red lines firmly on either side. A broad coalition of more than 100 countries continued to press for binding measures to reduce production, regulate chemicals and mandate product redesign.

Opposing them were producer states, who insisted the treaty should focus only on downstream waste management and recycling, leaving production unaddressed.

Opposing them were producer states, who insisted the treaty should focus only on downstream waste management and recycling, leaving production unaddressed.

As in previous rounds of negotiations, any proposals that might limit business as usual were systematically vetoed. Efforts to bridge the divide stalled, and whole sessions were taken up with procedural disputes rather than substantive progress.

At the midway “stock-taking” plenary session on 9 August, many delegates made clear their belief that seeking consensus was a futile endeavour. They were instructed to plough on regardless.

The Chair’s gambit

As the talks entered their final stretch, with progress nowhere in sight, the Chair took the unusual step of introducing a compromise text of his own making. The move was intended to salvage at least a minimal outcome and prevent the talks from collapsing entirely. Yet its timing – unveiled late in the process, with almost no time left for negotiation – and its content – stripped of articles on production, chemicals and health and any legally binding language – proved divisive.

Many ambitious countries saw the text as a capitulation to the lowest common denominator. Producer countries, meanwhile, were still unwilling to endorse even these watered-down obligations. The gamble backfired: rather than finding common ground, the move increased frustrations. Diplomatic niceties were abandoned, as state after state called the text a “betrayal”, a “surrender” and a “mockery” of majority wishes.

With only hours left, the Chair was under huge pressure to find a new solution.

Collapse but not erasure

By this time, more than 60 ministers had already flown in order to get the deal done. Yet after a marathon final session that lasted almost 30 hours, a new and only slightly improved Chair’s text failed to get an agreement. The session was brought to an abrupt close. No clear roadmap was adopted beyond a vague commitment to continue discussions.

The sense of anticlimax was overwhelming. After two and a half years and $40 million poured into negotiations, governments were no closer to resolving the core question of whether the plastics treaty will address the problem at its source, or simply manage waste at the margins.

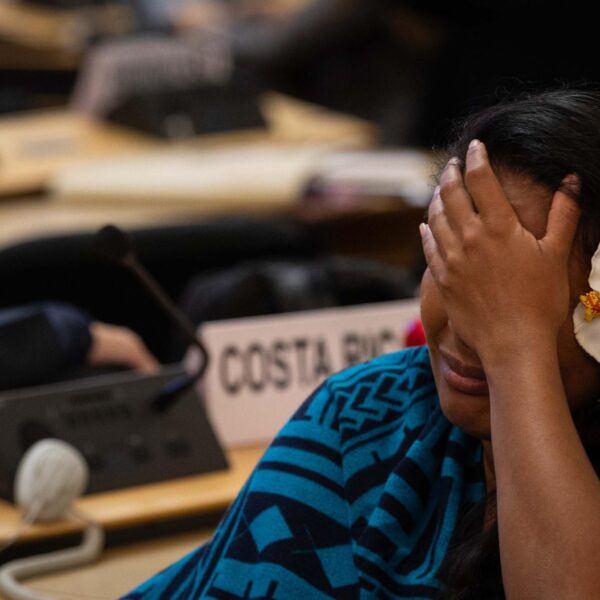

Exhausted negotiators and observers could not disguise their deep disappointment.

Yet it was also clear that, had the compromise text been adopted, it would have locked us in to a weak treaty with no power to curb plastic pollution. Time, money and energy had certainly been wasted trying to reach unanimity, but valuable work had nonetheless been done. The foundations of a strong treaty are in place, ready to be revived when the political will emerges.

Where next?

Two main paths now lie ahead. The first is to continue negotiations at an INC-5.3, but currently there is no budget, nor any mandate for this. And, for ambitious countries to return, UNEP would need to provide assurances of procedural reform. Enforcing the rule that allows voting on substantive matters remains the only way for them to move forward within the INC framework. Doing this would however risk a walkout by producer states – and potentially then a wider crisis for UNEP and the multilateral system.

A more promising option is the formation of a “coalition of the willing”, as used to create the global treaty banning landmines in Ottawa in 1996. Ambitious states could negotiate an agreement outside the UN framework, setting binding production limits and chemical phase-outs. Obstructors would be left out, while still feeling the effects of the agreement through trade and market forces. UNEP could be involved in the treaty’s implementation, ensuring they remain relevant.

This option is made easier by the fact that, over the course of the negotiations, progressive states have already developed a series of conference room papers (CRPs). These are official proposals for text that could become the building blocks of a strong treaty. More than 100 countries signalled support for ambitious CRPs at INC-5.2.

This option is made easier by the fact that, over the course of the negotiations, progressive states have already developed a series of conference room papers (CRPs). These are official proposals for text that could become the building blocks of a strong treaty. More than 100 countries signalled support for ambitious CRPs at INC-5.2.

This means that there is a solid shared foundation to return to when talks resume.

Civil society groups emphasise that political momentum can still be built. But pressure from outside the negotiating halls will be critical. Without stronger mobilisation to counterbalance industry lobbying, governments may continue to stall.

Less an ending than a reset

INC-5.2 was not the breakthrough many hoped for, but nor was it the disaster some feared. By refusing to endorse a toothless compromise, governments kept alive the chance for a treaty that can truly end plastic pollution.

The challenge now is to convert the foundation of existing CRPs into a finished text, whether through procedural reform at UNEP or a coalition of the willing elsewhere. The coming months will determine whether governments have the courage to deliver a treaty fit for purpose, or squander the chance to confront one of the defining environmental challenges of our time.

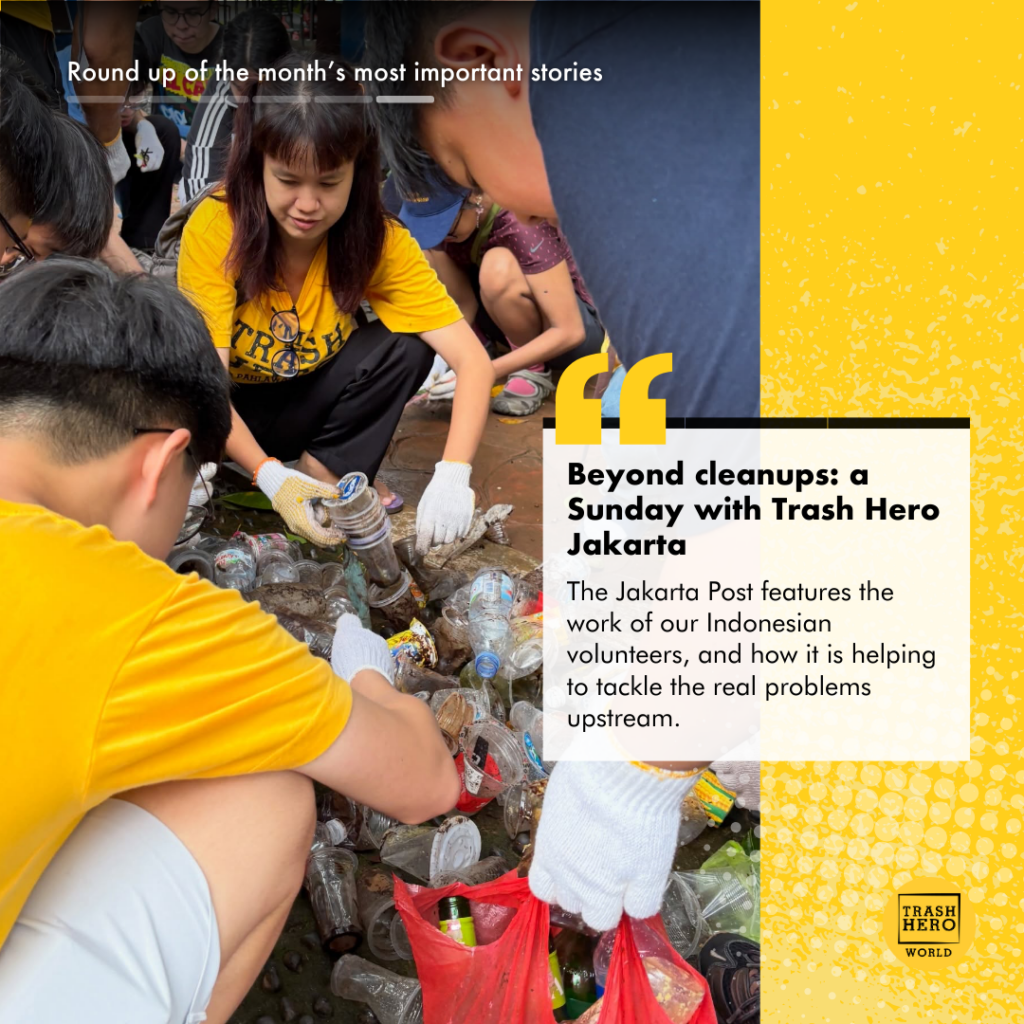

Trash Hero at the treaty talks

As a UNEP-accredited observer, Trash Hero is able to attend all INC meetings. We join our colleagues in the large civil society delegation that advocates for strong and just measures in the treaty and support the communications and advocacy work done in and around the meeting venue.

read more

Mostly As – The Networker

Mostly As – The Networker Mostly Bs – The Organiser

Mostly Bs – The Organiser Mostly Cs – The Motivator

Mostly Cs – The Motivator Mostly Ds – The Collaborator

Mostly Ds – The Collaborator